The Intricate Symphony of Digestion: A Deep Dive into the Human Digestive System

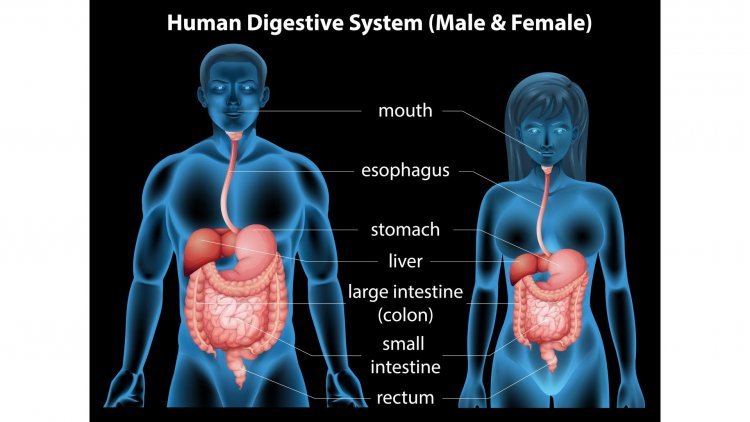

The human digestive system is a marvel of biological engineering, orchestrating a complex symphony of processes that transform food into essential nutrients and energy. This intricate system is responsible for breaking down the food we eat, absorbing nutrients, and expelling waste, all while maintaining a delicate balance to keep our bodies functioning optimally. From the moment food enters our mouth to the final stages of waste elimination, each component of the digestive system plays a critical role in ensuring our health and well-being. Let’s embark on a journey through this fascinating system, exploring its components, functions, and the ways in which it maintains harmony within our bodies.

The Journey Begins: The Mouth and Esophagus

The digestive process starts with the act of eating, where the mouth plays a pivotal role. When food enters the mouth, it is broken down by chewing, a process that physically reduces food into smaller pieces. Saliva, produced by the salivary glands, begins the chemical digestion by breaking down carbohydrates into simpler sugars. Saliva also contains enzymes such as amylase and lysozyme, which further aid in digestion and help prevent infections.

As the food is chewed and mixed with saliva, it forms a bolus—a soft, rounded mass that is ready to be swallowed. The process of swallowing, or deglutition, is a coordinated effort involving the muscles of the mouth, throat, and esophagus. The bolus is pushed to the back of the throat and into the esophagus, a muscular tube that connects the mouth to the stomach.

The esophagus functions as a conduit, using a series of wave-like muscle contractions known as peristalsis to propel the bolus toward the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES), a ring of muscle at the end of the esophagus, acts as a gateway between the esophagus and the stomach. It opens to allow food to enter the stomach and closes to prevent the backflow of stomach acid and contents.

The Stomach: A Gastric Grinder

Upon entering the stomach, the food is subjected to a highly acidic environment, which is crucial for further digestion. The stomach secretes gastric juices, which include hydrochloric acid (HCl) and pepsin. HCl creates an acidic pH that helps break down proteins and activates pepsin, an enzyme that begins the digestion of proteins into smaller peptides.

The stomach is also equipped with powerful muscles that churn and mix the food with gastric juices, forming a semi-liquid mixture known as chyme. This mechanical digestion ensures that the food is thoroughly mixed with digestive enzymes, enhancing nutrient breakdown. The stomach lining is protected from its own acidic environment by a thick layer of mucus, which prevents self-digestion and irritation.

The pyloric sphincter, located at the end of the stomach, regulates the passage of chyme into the small intestine. This sphincter opens in a controlled manner, allowing small amounts of chyme to enter the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine, for further digestion and absorption.

The Small Intestine: The Nutrient Absorber

The small intestine is the site where the majority of nutrient absorption occurs. It is a long, coiled tube divided into three sections: the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. Each section plays a unique role in digestion and absorption.

The Duodenum is the first section of the small intestine and is responsible for receiving chyme from the stomach as well as bile from the liver and pancreatic juices from the pancreas. Bile aids in the digestion of fats by emulsifying them into smaller droplets, which increases the surface area for lipase, the enzyme responsible for breaking down fats. Pancreatic juices contain enzymes such as amylase, lipase, and proteases that further break down carbohydrates, fats, and proteins respectively.

The Jejunum is the middle section of the small intestine, where most nutrient absorption takes place. The inner walls of the jejunum are lined with villi and microvilli, tiny finger-like projections that increase the surface area for nutrient absorption. These structures facilitate the transfer of nutrients from the digestive tract into the bloodstream.

The Ileum is the final section of the small intestine and continues the absorption of nutrients that were not absorbed in the jejunum. It also absorbs vitamin B12 and bile acids, which are recycled back to the liver for reuse. The ileum ends at the ileocecal valve, which regulates the flow of material into the large intestine.

The Large Intestine: Water Reclamation and Waste Formation

The large intestine, or colon, plays a crucial role in the final stages of digestion. It is responsible for absorbing water and electrolytes from the remaining indigestible food matter, transforming it from a liquid into a more solid form. This process is essential for maintaining fluid balance and preventing dehydration.

The large intestine is divided into several parts: the cecum, colon (ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid), rectum, and anus. Each section has distinct functions in the absorption and elimination processes.

The Cecum is the initial pouch-like section of the large intestine where the ileum connects. It serves as a conduit for the chyme from the small intestine and houses the appendix, a small, tube-like structure whose role is not entirely understood but is believed to have immune functions.

The Colon is the largest part of the large intestine and is responsible for the absorption of water and electrolytes. It is divided into four regions:

- Ascending Colon: Located on the right side of the abdomen, it absorbs water and electrolytes from the chyme.

- Transverse Colon: Extending across the abdomen, it continues the absorption process and helps in the formation of feces.

- Descending Colon: Located on the left side, it stores the formed fecal matter until it is ready for elimination.

- Sigmoid Colon: The final part of the colon, leading into the rectum, where the feces are compacted further before being expelled.

The Rectum serves as a temporary storage site for feces. It signals to the brain when it is time for defecation. The rectum's lining contains stretch receptors that detect the presence of fecal matter and initiate the urge to defecate.

The Anus is the final part of the digestive tract and is equipped with two sphincters—the internal and external anal sphincters. The internal sphincter is involuntary and maintains continence, while the external sphincter is under voluntary control, allowing for the controlled release of feces during defecation.

Digestive System Regulation: Hormones and Nervous Control

The digestive system is intricately regulated by a combination of hormonal signals and nervous system control. This regulation ensures that digestive processes occur smoothly and efficiently.

Hormonal Regulation: Several hormones play key roles in managing digestive functions:

- Gastrin: Secreted by the stomach, gastrin stimulates the production of gastric acid and pepsin, promoting protein digestion.

- Cholecystokinin (CCK): Produced by the small intestine, CCK stimulates the release of bile from the gallbladder and pancreatic enzymes, aiding in fat and protein digestion.

- Secretin: Also released by the small intestine, secretin regulates the release of bicarbonate from the pancreas, neutralizing stomach acid and creating an optimal pH for enzyme activity in the small intestine.

- Ghrelin: Known as the hunger hormone, ghrelin stimulates appetite and increases food intake.

Nervous Control: The digestive system is also regulated by the autonomic nervous system, which includes:

- The Sympathetic Nervous System: Activates the "fight or flight" response, reducing digestive activity and diverting resources to other systems in times of stress.

- The Parasympathetic Nervous System: Promotes the "rest and digest" response, enhancing digestive processes and increasing motility and secretion.

The enteric nervous system, often referred to as the "second brain," is a complex network of neurons embedded in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract. It operates independently of the central nervous system and regulates various digestive functions, including peristalsis and enzyme secretion.

Common Digestive Disorders

The digestive system is susceptible to various disorders that can disrupt its normal function. Some common digestive disorders include:

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD): A condition where stomach acid frequently leaks into the esophagus, causing symptoms such as heartburn and acid regurgitation.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A functional gastrointestinal disorder characterized by symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and altered bowel habits.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): Includes conditions like Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, which involve chronic inflammation of the digestive tract.

- Peptic Ulcer Disease: Caused by the erosion of the stomach or duodenal lining due to excess stomach acid or infection with Helicobacter pylori bacteria.

Maintaining Digestive Health

To maintain a healthy digestive system, consider the following tips:

- Balanced Diet: Consume a diet rich in fiber, fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins to support healthy digestion.

- Hydration: Drink plenty of water to aid in digestion and prevent constipation.

- Regular Exercise: Engage in physical activity to promote healthy bowel function and reduce stress.

- Probiotics: Incorporate probiotic-rich foods or supplements to support a healthy balance of gut bacteria.

The digestive system is an extraordinary and finely tuned network that ensures the body’s nutritional needs are met while efficiently managing waste. Understanding the complex interactions between its various components helps us appreciate the delicate balance required for optimal digestive health. By maintaining healthy lifestyle habits and being mindful of potential disorders, we can support the digestive system’s crucial role in overall well-being.

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. If you have any health concerns or are experiencing symptoms, it is important to consult with a healthcare professional, such as a doctor or clinic, for proper diagnosis and treatment. Always seek the advice of your doctor or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Do not disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

What's Your Reaction?