From Past to Present: Tuberculosis in the Modern Era

Tuberculosis (TB), caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, remains one of the most significant infectious diseases globally. Despite advances in medical science, TB continues to pose a formidable challenge to public health systems worldwide. This article provides an in-depth examination of TB, encompassing its epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnostic modalities, treatment regimens, prevention strategies, and the ongoing efforts to combat this ancient scourge.

Epidemiology

TB affects individuals of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds, but its burden is disproportionately borne by low- and middle-income countries. In 2019, an estimated 10 million people developed TB, with approximately 1.4 million deaths attributed to the disease. Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia carry the highest burden of TB, with factors such as poverty, overcrowding, malnutrition, HIV co-infection, and inadequate healthcare infrastructure contributing to its persistence in these regions. Vulnerable populations, including migrants, prisoners, and individuals living in urban slums, are particularly susceptible to TB due to socioeconomic disparities and limited access to healthcare.

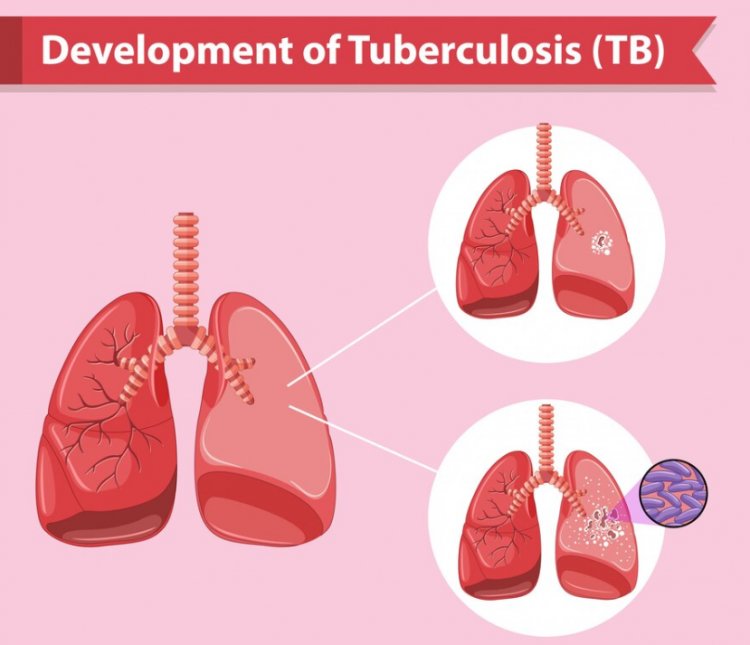

Pathogenesis

M. tuberculosis, the causative agent of TB, is a highly adaptable bacterium capable of surviving in a variety of environmental conditions and evading host immune responses. Following inhalation of infectious aerosols containing M. tuberculosis, the bacteria are engulfed by alveolar macrophages in the lungs, where they replicate and establish infection. The host immune system mounts both innate and adaptive immune responses to control the infection, leading to the formation of granulomas, which serve as a barrier to bacterial dissemination. However, in some individuals, the bacteria evade immune surveillance, leading to active TB disease characterized by tissue damage, inflammation, and clinical symptoms.

Clinical Manifestations

TB can manifest in various forms depending on the site of infection and host immune status. Pulmonary TB is the most common presentation, characterized by symptoms such as cough, sputum production, chest pain, hemoptysis, fatigue, weight loss, fever, night sweats, and loss of appetite. Extrapulmonary TB occurs when the bacteria spread to other organs, resulting in clinical syndromes such as lymphadenitis, pleurisy, meningitis, pericarditis, skeletal TB, genitourinary TB, and gastrointestinal TB. HIV co-infection significantly increases the risk of developing active TB and complicates its clinical management.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing TB requires a multifaceted approach that includes clinical evaluation, medical history, physical examination, and laboratory testing. Common diagnostic tests include the tuberculin skin test (TST), interferon-gamma release assays (IGRAs), chest X-rays, sputum smear microscopy, culture-based methods, and molecular tests such as nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs). Microbiological confirmation of TB is essential for initiating appropriate treatment and preventing further transmission of the disease. Rapid molecular assays, such as the Xpert MTB/RIF assay, facilitate the detection of TB and rifampicin resistance in resource-limited settings.

Treatment

TB is treatable and curable with a combination of antibiotics administered over a specified duration. Standard treatment for drug-susceptible TB involves a four-drug regimen consisting of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol, administered for six to nine months. Directly observed therapy (DOT) ensures treatment adherence and improves treatment outcomes, particularly in high-risk populations. Drug-resistant TB, including multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB) and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB), requires individualized treatment regimens with second-line drugs, which are more toxic, less effective, and often associated with longer treatment durations. Adverse drug reactions, drug interactions, and the emergence of further drug resistance pose significant challenges to TB treatment.

Prevention

Preventing the spread of TB requires a comprehensive approach that addresses both individual and population-level determinants of TB transmission. Key prevention strategies include early detection and treatment of active TB cases, infection control measures in healthcare settings, contact tracing and screening of high-risk populations, provision of isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) to individuals with latent TB infection, and vaccination with the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine. While the BCG vaccine provides partial protection against severe forms of TB, its efficacy varies widely across different populations and settings. Innovations in TB vaccine development, such as recombinant BCG strains and novel subunit vaccines, hold promise for improving TB prevention efforts in the future.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress in TB control over the past century, several challenges persist, hindering efforts to eliminate the disease globally. Drug-resistant TB, inadequate access to diagnostics and treatment, healthcare disparities, stigma associated with TB, funding gaps, and the intersection of TB with other infectious diseases such as HIV pose formidable challenges to TB control programs. Achieving the ambitious targets outlined in the WHO End TB Strategy, including a 90% reduction in TB incidence and a 95% reduction in TB deaths by 2035, requires sustained political commitment, increased investment in research and development, and multisectoral collaboration to address the social, economic, and environmental determinants of TB.

In conclusion, Tuberculosis remains a complex and dynamic public health challenge with profound social, economic, and health implications worldwide. Efforts to combat TB must be holistic, addressing the biological, social, and structural determinants that drive TB transmission and perpetuate health inequities. Through collaborative action, innovation, and investment in health systems strengthening, it is possible to accelerate progress towards a world free of TB and ensure health for all.

#Epidemiology #Pathogenesis #ClinicalManifestations #Diagnosis #Treatment #Prevention #ChallengesAndFutureDirections #PublicHealth #TBControl #HealthEquity #GlobalHealth #HealthSystems #InfectiousDisease #HealthcareAccess #TBPrevention #EndTB #HealthForAll

Disclaimer:

The information provided in this article is for educational purposes only and should not be considered medical advice. If you have any health concerns or are experiencing symptoms, it is important to consult with a healthcare professional, such as a doctor or clinic, for proper diagnosis and treatment. Always seek the advice of your doctor or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Do not disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

What's Your Reaction?